What I’m Playing: Dante

by

Sweet! This guy?

Nope. This guy.

Dante? Awesome! I’ve always wanted Brent to review a game from the Devil May Cry series! Which one did you play?

Er… well, let me explain. I wanted a space with my new website design to talk about video games—I love them. But I also want to, from time to time, engage with other media. “What I’m Playing?” fits in a shorter space than “What form of media is Brent playing or reading or watching, and what particular title currently, and what is his take on that?”

So, uh, really this sidebar is “Brent’s Brain at Play” … so, yeah, it’s false advertising. Sorry.

I’ve just re-read The Divine Comedy for the first time since four miserable weeks in 1995. Miserable not because I hated Dante. I read the Dorothy Sayers translation in terza rima, and I loved much of it. The misery came from the class: Freshman Honors English, semester 1. This was my introduction to college. One semester, one class: 4,200 pages of reading.

I still believe this was the class that convinced the smartest student in the college—I’m talking ‘pun in Latin and expect others to laugh along with you’ smart—to drop out and become a priest. Little known fact: that kid punched me in the face once. (A little known fact that will doubtless come up when he’s up for canonization—he was a pretty darn good guy. Is still, I assume!) It was not the only fight I got into in college, oddly enough, though it was the only one where I didn’t hit back… So I guess you could say I… lost?

But c’mon, you try to hit back after a future pope punches you. If the word ‘discombobulating’ had been invented for any legitimate purpose, it would have been for that moment. (But that’s a pure hypothetical. Don’t combobulate if you hope to copulate, nerds.)

But I digress. Every student in Honors English 101 had a B or lower. (B- here.) Our professor was a poet. He really liked the word “wen”. No further explanation needed, right? The end of the semester was fast approaching. Panic set in for all these kids who’d never earned less than an A- in their 18 blesséd years, sir, by my troth!

The professor said we could add AN ENTIRE LETTER GRADE to our grade if we… outlined the entire Divine Comedy. That’s… a trilogy of epic poems.

It was an assignment that would later save my soul. But that’s another story.

Imagine thirty sweating honors class freshmen, some of whom had scholarships riding on their GPA, others—far more importantly—had their entire self-worth riding on their GPA. All of us faced Thanksgiving Break with the shame of a B. It had just become Thanksgiving “Break”.

There were three weeks from Thanksgiving until finals, when the assignment was due. Three weeks in the inferno—or, if one paced oneself correctly, one would only spend one week in Inferno, one in Purgatorio, and the last in Paradiso.

Oh, let me tell you, how those freshmen rejoiced their way through Paradiso. Well, maybe the final canto. Paradiso’s a bit of a slog, dramatically.

Want to see a textbook definition of subclinical triggering? Just whisper “Bernard of Clairvaux” to any veteran of Dr. Sundahl’s H ENG 101.

*insert meme here*

The angel on my right shoulder: *No, really, don’t.*

All this is prologue. (Dizzam, bruh, that’s some Jordan-esque level prologue.)

On to the review.

I was glad to see that after 20 years, Dante hasn’t become dated. Ages well, Ol’ Danny Alighieri. Okay, fine. I should say, “more dated”. One thing in particular struck me repeatedly about Dante, reading him now as a 39-year-old fantasy writer, versus reading him as an 18-year-old college freshman, and I mean so oft-repeated I felt like my face belonged to a P.I. in a noir novel–I mean repeatedly like the bass thunder from the stereo in a 75hp Honda owned by that pepperoni-faced dude who thinks he’s auditioning for Fastest and Even More Furiousest Than Evar:

The chutzpah. The sheer audacity. Dante was writing the work without which he would be forgotten by most everyone except Italian lit majors. He’s coming into this famous but soon to be forgotten, like the English Poet Laureate Robert Southey–you’ve heard of him, right? No. So before Dante’s written his Great Book, he presumes himself into the company of the all-time greats. (He deserves it, but he jumps into that place like that kid challenging Mario Andretti to a quick couple laps for pink slips.)

But not only that. He, a Christian (if one who finds himself lost along the Way in the dark wood of middle age), readily consigns foes and even acquaintances—some not yet dead, if I remember correctly—to Hell. If there’s one thing the modern mainstream Christian doesn’t do, it’s to presume the eternal destination of others. As C.S. Lewis said, (paraphrasing) “When we get to Heaven, there will be surprises.” That lack of presumption is bolstered on our culture’s favorite partial Scripture “Judge not lest ye be judged” which goes on “For in the same way you judge others, you will be judged, and with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.” Most Christians today are like, “Yeah, I’d prefer a really lenient measure, thanks. So I’ll just not presume to judge anyone else, either. Plus, not judging at all gets me thrown out of way fewer parties.” Dante, not so much. He’s like, “This pope from a few years back? Totally burning in Hell, right now. Look at the evil he did!”

Dante does this while, as far as I can tell (as a non-medievalist, and no longer even a Roman Catholic) remaining himself orthodox. He doesn’t question the pope’s authority as it was understood then. Check this example out: that evil pope who himself is burning in hell? He’d corrupted one of his own courtiers, who had previously been some kind of shady guy, but repented, turning his back on all the evil he’d done earlier in his life. (Think like Godfather 3.) The kicker? Evil Popey makes him go back! (“I try to get out and the Pope (!) keeps pulling me back in!”) Evil Pope gets him to betray some folks, by promising our repentant Michael Corleone, “Hey, yeah what I’m asking you to do is evil, but I’ll forgive you for all this evil you do for me. I’m the Vicar of Christ, so I can totally give you an Evil Pass.” So the courtier does said evil stuff. And gets ‘pardoned’.

Now the demons in hell that Dante encounters are super pissed, because “Hey, that guy should totally belong to us! He did evil stuff!”

But Dante DOESN’T question that the evil pope effectively uses a loophole to get around God’s perfect justice. Nope. That courtier guy is heading for heaven—except the demons later tricked him into committing suicide by demons, a sin for which the pope apparently forgot to preemptively forgive him for.

This whole episode is listed as proof that the pope was evil: he used his authority to pervert eternal justice. That’s really, really bad. Later Protestants would say, “This is redonkulus! No one gets to use a loophole to escape God! That’s the whole point of eternal justice: often on Earth justice isn’t served, but we can deal with that because we know no one can escape God’s justice. If your doctrine lets people fool God, your doctrine is wack, yo. [Also, that you have Evil Popes in the first place seems to point out a problem in your system.]”

Dante’s audacity though, goes further than merely presuming himself in the company of the greatest of the greats, and also being comfortable judging the quick and the dead: Dante sets out to out-epic Homer and Virgil.

Homer [with a battered old harp, ratty beard, and mismatched sandals–dude’s blind, give him a break on the fashion policing, people]: “Friends, Achaians, countrymen, lend me your ears. I’mma tell you about big war and a big voyage with the ideal Greek man.”

Homer’s poetry and story-telling, his nuance and his imagery would capture and define an entire culture, and deeply influence many others through the present. It’s hard to overstate his impact.

Virgil [strides forth in a solid gold toga, taking a bit of snuff from a slave]: “No offense, old sport, but your hero was bollocks, Homes. He was actually the bad chap, and not nearly as wonderful as you make him out to be. Let’s talk about that Trojan War thing, and I’ll subvert the Hades out of your narrative.”

Oh snap.

Virgil is a master of poetry and storytelling who is self-consciously telling the story of an entire people and their founding mythos, (small) warts and all (sorry ’bout that, Dido! a real James Bond always loves ’em and leaves ’em… burning!). Virgil meant his epic to be studied and admired by audiences high and low, and he meant to define his Romans as the best of the best. Sort of “the arc of history is long, but it bends toward Rome.”

Dante [ambles up in a Led Zeppelin t-shirt and bell-bottoms]: “You guys are far out. Wish I could have heard your stuff, Home-bre, I’ve heard it’s real groovy, but the Saracens haven’t invaded yet with their hippie zeal to give us the LP bootleg translations of your work from the Greek. Sing it for me sometime. I’m sure I’ll dig it. Anyway, bros, thanks for inviting me to your drum circle here, but never start a land war in Asia unless you’re the Mongols, never get in a wit-fight to the death with a guy named Westley, and never, ever invite John Bonham to your drum circle. You guys thought small. Nah, it’s cool and everything, but really? Some guy on a boat? Some other pious guy on a different boat who lost a war to the first guy? I’mma let you finish swiftly here, but I’m going to tell the story of all creation, do world-building that includes the entire universe—both the physical and metaphysical worlds: earth, hell, purgatory, and heaven, AND show how my main man Jesus changed everything, aided in my quest by numerous holy Jesus groupie chicks and the spirit of Virgil himself. Hope you’re down with that, Virg. I mean, you’re an Italian, I’m an Italian, we’re pretty much bros, but I’m like your intellectual successor and stuff? Oh yeah, and because I’m after Christ, I really have an unfair advantage on you, because you were the bee’s knees. Seriously, love your stuff, I even own the b-sides of your pastoral poetry. So if I’m a little better than you, it’s purely happenstance: You came before Ludwig drums and Remo drumheads, man! If someone told you ‘More cowbell!’ you’lda been like ‘A cowbell? In music? What’s next, balancing a shield on a post and banging on it with a stick?!’ By the way, I use Paiste cymbals. I’ll show you later.”

That story of all creation includes the pagans. Dante also sets about to reconcile, or at least appropriate, the gods and monsters of antiquity—though sometimes not very successfully. I’m like, Hey, big D, if some of the figures of Greek mythology are real, are all of them? If they’re real and they did some of the stuff we’ve heard they did, where was God in that? Are these all actually just demons just playin’ around? Fess up, c’mon. You can tell me, buddy, I understand. You just wanted monsters, didn’tcha? You got stuck on that one part and were like, How can I get Dante and Virgil out of this one? Oh, I know! A big ass dragon flies up out of the pit, scares the bejeepers out of them, and then totally lets them become the Dragonriders of Burn and head on down further!

Oh, did I mention that while doing all this, Dante maintains that he’s writing on four levels at once: 1) The literal (which, you know, literally means the literal, the stuff that happens—hey, I write on that level too!). 2) The allegorical (that is, there’s what he calls “truth hidden beneath a beautiful fiction”) so being lost in a dark wood in your middle years might be an allegory for getting lost in your life, or even a mid-life crisis. 3) The moral (which explores the ethical implications of a work of fiction) so what do you think about Odysseus sitting on the beach crying to go home to his wife every day, and then banging goddesses every night? What do you learn about the power of hope or forgiveness when Luke Skywalker confronts Darth Vader? That’s the moral level; and 4) The anagogical. Yeah, you’re not going to see this word unless you’re talking about Dante, I’d guess. I had to look it up again. I was honestly proud of myself for merely remembering the word. The anagogical is a level of spiritual interpretation. This is when the work captures something that is eternally true. In a Platonic sense, it would be when you step out of the cave and instead of looking at shadows on the wall of thing that are True, you look at the things themselves. For Dante, this is of course expounding scripture in a way that captures “a part of the supernal things of eternal glory”. (Supernal: being of, or coming from, on high.)

This is the level where you say, the characters Dante and his guide Virgil are hiking up Mt Purgatory, but Virgil is literally Virgil, a great poet who lived before Christ and thus is a pagan, so when Dante and Virgil get to the top of Mt Purgatory, Virgil can’t get into Heaven—you need Jesus for that. “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life. None come to the Father except through me”. (Virgil’s not exactly being punished for being a pagan; he gets to hang out talking with all the other awesome pagans forever.) But Virgil is ALSO an embodiment of Reason, so when Virgil and Dante reach a rad curtain of fire up on the top of Mt Purgatory, Virgil can (as Reason) say, “Bro, you got this. You know there’s people on the other side. You know this is the only way to get there. You therefore know they jumped through this curtain. Ergo, you won’t get fried. Probably. Well, at least not everyone who jumps through gets a thermite sun-tan.”

But Reason can’t go through that curtain himself. The thing that makes you jump through a curtain of fire isn’t, ultimately, reason. Reason can’t get you to Heaven. Thus, the anagogic lesson is that belief is, ultimately, an act of the will. Or, in the common phrase of which this scene may be the origin, one must take a Leap of Faith.

Did I mention Dante’s doing this while writing poetry? And apparently his poetry is pretty good? (Not knowing Italian, I can’t say. The Sayers translation I read in college was way more beautiful than the Clive James version I listened to this time. Sorry, Clive, personal preference.)

Now, I should probably address the world-building, too, seeing how world-building is something fantasy writers ought to know something about. (Yes, hecklers in the back, I hear you. Notice the caveat ‘ought to’? Now run along and play. With scissors.) In the mind of your inconsistently humble correspondent, Dante’s world-building is bold, presumptuous, brilliant, and a blithering mess.

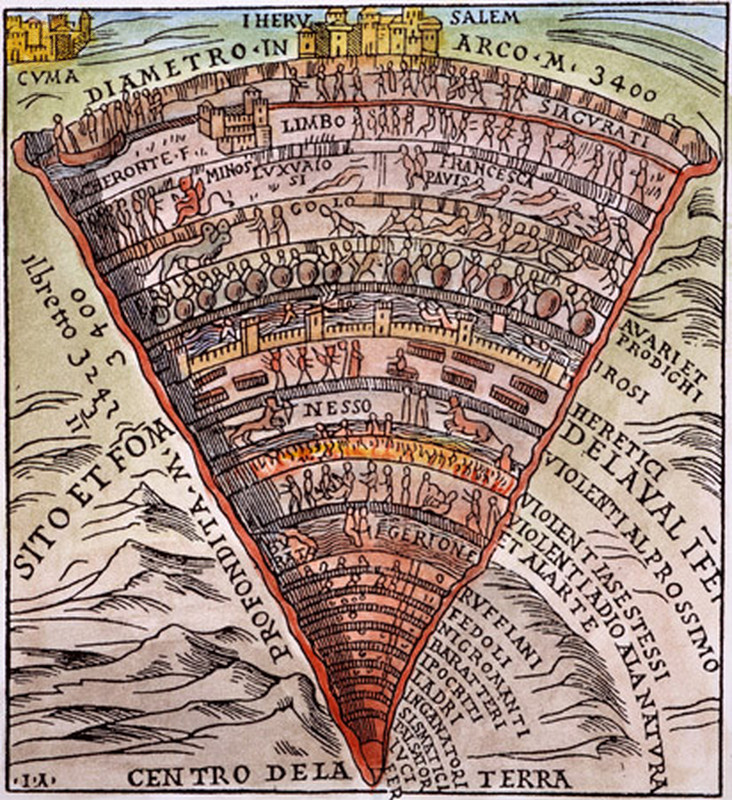

Whereas Dante’s treatment of pagan mythology would likely appeal to the common reader and just as likely outrage scholars who knew enough to ask questions, in his world-building, he seems to completely ignore the common readers, and go straight for the art- and map-geeks. You’ve probably seen those elaborate medieval drawings of the world Dante lays out.

Woodcut from a Venetian edition of the Divine Comedy, c1520.

(I don’t even know if most of them are faithful to the text or even agree with each other, other than the order of the circles of hell and the like.) On the one hand, this world-building is ingenious. Stunning. (Anyone know if he borrowed most of this, or invented most of it? I know he was synthesizing a lot of speculation and Christian cosmology, but I don’t know how much of his work on this is original.)

It all hangs together, literally and symbolically and morally. Satan is at the center of gravity? Like, literally? At first, you’re like, “Huh?”

Well, he’s got to have his head visible in hell; he’s the king there, and he’s got to be scary. How scary is a guy with buried head-down with his butt in the air like a North Dakotan bike rack? (Sorry, old Montanan North Dakota joke there.) But when you think further, well, hell has inverted values, so after you come past him at the center of gravity, and into a vast crater–he left a giant crater when he was thrown out of heaven. Of course he did! And here he IS head down and not so scary, but he’s also head down because he’s buried in his sin. He’s at the bottom of a pit. Of course he is! He’s denied the light of heaven, his face must be buried. And so on.

But most of the things that I caught on this second listening, I caught only because of the art I’d seen, and the explication of college professors and footnotes back when I’d read it before. Those professors taught me that the common way for people to experience a book during Dante’s time was most usually that someone would stand and read it to everyone else. (Audiobooks go WAY back.) This is a terrible way to experience what he’s doing, though.

When you only listen to the Divine Comedy, there’s no way for you to understand a lot of the imagery. Not a real quote, but a realistic one: “Then I turned left 90 degrees, and saw, up at the point where the sun was crossing the mountain, another path veering to starboard under the sign of the Cygnus at the fourth hour of the morning” oh, and time moves differently in Purgatory. Or something. I still don’t get that part.

This kind of world-building doesn’t work at all for the medium. Certainly the first listeners wouldn’t have any art or maps to help them figure this stuff out in real time, while the reciter continues reciting the poetry describing this weird journey. So it’s definitely weird, it’s opaque, and it’s kind of bad art–at least, bad world-building for what is, at core, more of a travelogue than an epic adventure.

But it works… for the artists and the map-geeks, who fan art the hell out of it.

Now, I call Dante’s world-building presumptuous because leaving the explanations for all the weirdness intelligible ONLY to those geeks ONLY works because Dante was famous. If he hadn’t been famous already, people would go, “Huh, this doesn’t make sense to me. So it probably doesn’t make sense. What garbage.”

So it kind of works in the way Ikea instructions work–if you’ve got a bunch of Ikea engineers in your living room to help you out: “Oh, that was a concise way to explain that… now that you did it all for me.”

Dan, my boy, that is some… what’s the term for accurate hubris? Oh, self-confidence. I guess it’s still that even when the SELF-CONFIDENCE IS GIANT, YO!

All this! Look at all that! He’s doing all that… and more. At the SAME time! All that, and then… Dante flinches.

Dante gets daunted.

Bro!

Bro.

When this pilgrim who has had to fight past so many lesser demons (using his special access badge that says, I’m-on-a-holy-mission-one-of-the-roadies-from-JC-and-the-Sonshine-Band-says-it’s-cool) finally makes it to Satan’s circle and crosses the frozen lake of Coccytus, do you know what Satan says?

Do you know how Satan addresses the first non-traitor to visit Satan since he was thrown out of Heaven? Satan himself… just doesn’t notice. Sure, the big guy is busy gnawing on Judas, Brutus, and Cassius but he’d been gnawing on those guys for thirteen hundred years!

But nope. Satan says nothing. There’s no, “Yeah, I let you come all the way down here by my satanic will. It was all a trap. Now you can rot with the worst of them. I am literally going to eat your idiot face for eternity!”

There’s no big rescue from the monstrously huge arms and hands as that giant is stuck in the frozen lake of Coccytus. No last minute rescue by an angel.

Nope, Satan just doesn’t notice. Even when Dante grabs onto his hairy ass and climbs around him through the center of the universe where gravity reverses itself and climbs out to go to Mt Purgatory, literally past his butthole. Satan. Doesn’t. Notice. Doesn’t notice the man playing George of the Jungle on his hairy hip. And climbing…Past. His. Butt.

Weaksauce, Ali D!

Lotta buildup to go limp at the finish! It’s like you’ve never played a video game in your life.

I’m sure someone can defend it. Great literature of this magnitude will always inspire defenders. But just because something is great in many, many ways doesn’t mean it’s great in every way. To me, this reads as a failure of nerve, or a failure of poetry, or the latter and then the former.

Because I can see this: Dante’s like, Man, when I write my Satan, it’s got to be good. I mean, like the best poetry ever. He was the highest of the angels. He was so beautiful, and his fall so epic, my lines describing him must be amazing. They’ve gotta be best I’ve ever written.

Maybe he couldn’t come up with those lines. Too much pressure. Or maybe he did, and then got nervous that he was giving the best lines of his career… to the Devil himself. (Milton, later, wouldn’t flinch on this count–good way to one up old D.) But Dante flinches, or fails, either as a dramatist or as a poet.

In only a few places is Dante (the character) actually sort of threatened by all the terrible demons he confronts. Mostly, he just kind of walks past. It’s like Dante (the real-life poet) was intuiting the interstices between a travelogue and an epic quest. Here, by walking past Satan and describing him, but never interacting, he falls back into travelogue. Here’s the difference: a travelogue is boring your neighbors with a two-hour slideshow of your trip to the Death Star; an epic quest is blowing it up before it blows your planet.

Granted, given that this is Satan, the character Dante isn’t going to do jack squat to Satan. On a literal, moral, or anagogic level, he obviously can’t. That’s a tough problem with the rubric Dante’s set up for himself. But Satan could at least interact with him so that it’s not also a dramatic failure. Satan could lie. Try to destroy him.

In Christian scripture, Satan’s a devouring lion, forever seeking to kill and destroy. Here he’s a fat kid gnawing on popsicles. Why not have Dante (the character) momentarily believe Satan’s lies? So much of fiction reaches its climax when there’s a symbolic or literal death. Here, in a story about everything in the universe, there’s nothing like that? Why not have Dante barely escape, rattled and fundamentally changed by his own encounter with ultimate evil?

Instead, it’s more like, “And this is another interesting thing we saw. Scary, huh?” This is viewing the T-Rex in Jurassic Park, if it never gets out of its enclosure. You tap on the glass and it roars, and you go home to a nice steak.

Missed opportunity, bro. You coulda been a contender. You coulda been somebody.

Scoot over at the drum circle, Danny boyo; you’re no John Bonham yet.

5 Stars–but only because I’m a forgiving critic.

You always have such fun with your writing. Can we, as readers, take this to mean that Dante’s interpretation (or lack thereof) of Satan informs your works? Perhaps why you get so real with your depiction of an alien and ultimate evil in “The Broken Eye”, particularly that “Great Library” scene?

That was a very engaging part, I might add. You did well on capturing the wonder and fear a currently lesser being would have, by comparison, to such monumental entities.

At any rate, thank you for sharing your take on Dante. As the ancient Romans say, wicked sick, my dude!

I can’t help but smile, laugh, and shake my head when I read the articles you write for fun. Usually your jokes are borderline “dad jokes” and that’s why I shake my head. This time though, I am shaking my head because I came to the end of this and wanted to hear more about Honors English 101.

Just think of the parallels you could have drawn- the class experience being a descent through Hell, a review within a review!

Such a wasted opportunity. Then again, if you were channelling your inner Jordan there are another 12 books to hear this story, right?

Yeah, but there was only Inferno in that class. No Purgatory, certainly no Paradiso. Sooo… not a sustainable metaphor. I like how you think, though. We certain drew some parallels ourselves!

OK, I’ll bite. You said: “I’m sure someone can defend it…To me, this reads as a failure of nerve, or a failure of poetry.”

But your criticism depends on two assumptions:

(1) You assume that meeting Satan is the climax of the story, a la blowing up the Death Star. But it’s not. Meeting Satan is a blip on the radar of Dante’s epic quest to behold the Holy Trinity.

(2) You assume that wanted his Satan character to be the best ever. But he doesn’t. Dante wants to show that satan, hell, and sin are *boring*. By depicting the would-be climax of the first part of his trilogy as an anti-climax, he communicates literally, allegorically, morally, anagogically that satan is ho-hum, nothing to see here.

(As a literary device, it’s also brilliant because the reader is spurred on, by the let down, to hope for a bigger climax at the end — which the reader gets.)

Dante is showing and actually making the reader to *feel it*, that it turns out “ultimate evil” is less interesting than a conversation with Virgil about love and free will (Purgatory 16 if memory serves) or a conversation with Beatrice about moonlight (Paradise 2). Satan is a non-entity, a spandrel, a nobody. After journeying through hell with Dante, the charm of the forbidden is gone, the delight in darkness is dead, the appeal of the impure goes poof.

And don’t try to dismiss my defense by saying “Great literature always stirs up defenders”, because I could turn the same line on you: “I’m sure there are critics; great literature always stirs up critics.” I won’t dismiss your argument on those grounds, but will discuss it on its merits — and so should you.

Nice! First, thanks for engaging, Keith. Let me argue in good nature: 1) “Meeting Satan is a blip.” No, it’s not. Not in the text, and certainly it shouldn’t be in anything I’d recognize as classic dramaturgy. Dante portrays Satan as HUGE. His mouths can hold entire dudes (that he’s gnawing on). You’re trying to make a molehill out of a mountain. Secondly, Satan is at the center of gravity itself. He is the literal center of hell, and of the odd zone of Purgatory (or not-yet-Purgatory? I’m not sure how it qualifies) where he is the center of the great pit he made when he fell. The highest of the angels and his fall has a physical representation here that is massively important. 2) If Dante wanted to show that Hell is ‘boring’, then he’s a far greater failure than anything I’ve alleged! What do readers actually finish of this trilogy? The first book. Some few finish Purgatory, most never finish Paradiso. Because it’s more and more boring as you go. 2b) “As a literary device, it’s brilliant because the reader is spurred on by the letdown.” This kind of defense is EXACTLY what I was talking about. ‘This part that sucks is actually brilliant because it sucks!’ This is not how humans work. When the climax of a narrative sucks, people don’t go to the sequel. And behold, this is exactly what happens with readers of Dante. 3) I actually think “I’m sure there are critics; great literature always stirs up critics.” is a TOTALLY fair line of attack. Great work gets judged by different standards than good work. Dante versus anything else published in Italy that year? He wins by a mile! But in comparing his own work as equal or better than the greatest works of Western literature, Dante puts himself on the critical bull’s eye. He invites being judged unfairly. I wouldn’t judge a debut novelist against GRRM; I wouldn’t judge GRRM against Homer. But Dante? He’s legitimately great, and he deserves the sharpest examination, the sharpest defense, and the sharpest attacks.

So. Is teia Michael Corleone? And Karris the pope?

Glad to confirm you’ve been an avid gamer; I have caught definite references to Bethesda’s classic game, Morrowwind, in several of your books. I saw an Island of Vos, a historical remark about the Urs ( Dagoth Ur being the main villain of course from Morrowwind), as well as many other place names familiar to me from the game. And people names too, if I remember correctly. I just saw they’ve released an online version of Morrowwind, Mr Weeks–I hope to see you there. If you find a player named Sevellak Trular, you’ll be meeting me. Once I buy the game in a few weeks time, anyway.